Norges Bank surprised markets with a rate cut to 4.25%

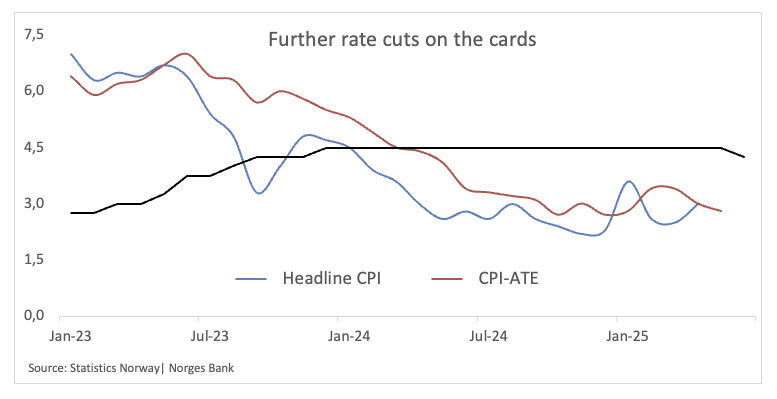

On Thursday, Norway's central bank (Norges Bank) surprised markets by announcing a 25 basis point reduction in its policy interest rate to 4.25%, signalling the expectation of further cuts due to a more favourable inflation outlook. The cut was the first one since 2020.

The Nordic central bank argued that the economic outlook is uncertain but indicated that if the economy evolves broadly as currently projected, the policy rate would be reduced further in the course of 2025.

Furthermore, Governor Ida Wolden Bache later indicated at a press conference that the policy rate might be reduced one or two more times by the end of the year, potentially bringing the interest rate down to either 4.0% or 3.75%.

Additionally, the Norges Bank indicated that by the end of 2028, the rate would likely be around 3%.

Market Reaction

The Norwegian Krone (NOK) depreciated to multi-day lows vs. the European currency on Thursday, lifting EUR/NOK to the proximity of the 11.6000 zone, adding to Wednesday’s uptick at the same time.

Central banks FAQs

Central Banks have a key mandate which is making sure that there is price stability in a country or region. Economies are constantly facing inflation or deflation when prices for certain goods and services are fluctuating. Constant rising prices for the same goods means inflation, constant lowered prices for the same goods means deflation. It is the task of the central bank to keep the demand in line by tweaking its policy rate. For the biggest central banks like the US Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB) or the Bank of England (BoE), the mandate is to keep inflation close to 2%.

A central bank has one important tool at its disposal to get inflation higher or lower, and that is by tweaking its benchmark policy rate, commonly known as interest rate. On pre-communicated moments, the central bank will issue a statement with its policy rate and provide additional reasoning on why it is either remaining or changing (cutting or hiking) it. Local banks will adjust their savings and lending rates accordingly, which in turn will make it either harder or easier for people to earn on their savings or for companies to take out loans and make investments in their businesses. When the central bank hikes interest rates substantially, this is called monetary tightening. When it is cutting its benchmark rate, it is called monetary easing.

A central bank is often politically independent. Members of the central bank policy board are passing through a series of panels and hearings before being appointed to a policy board seat. Each member in that board often has a certain conviction on how the central bank should control inflation and the subsequent monetary policy. Members that want a very loose monetary policy, with low rates and cheap lending, to boost the economy substantially while being content to see inflation slightly above 2%, are called ‘doves’. Members that rather want to see higher rates to reward savings and want to keep a lit on inflation at all time are called ‘hawks’ and will not rest until inflation is at or just below 2%.

Normally, there is a chairman or president who leads each meeting, needs to create a consensus between the hawks or doves and has his or her final say when it would come down to a vote split to avoid a 50-50 tie on whether the current policy should be adjusted. The chairman will deliver speeches which often can be followed live, where the current monetary stance and outlook is being communicated. A central bank will try to push forward its monetary policy without triggering violent swings in rates, equities, or its currency. All members of the central bank will channel their stance toward the markets in advance of a policy meeting event. A few days before a policy meeting takes place until the new policy has been communicated, members are forbidden to talk publicly. This is called the blackout period.